Okay, I did the math. If you use all 38 of the Live Templates for Java that are available out of the box in IntelliJ IDEA 2020.2, you will save your finger pads approximately 2092 presses of wear and tear, and that’s just each one once, the reality is likely to be substantially higher. I will caveat this by saying that I counted the unresolved variables, yours may be longer or shorter. Still, it’s impressive!

What are Live Templates?

Java has had its fair share of grief over boilerplate code and verbosity. You could type it out manually (boring), switch to Kotlin (it’s an option), or take a look at using IntelliJ IDEA to save you both time and effort.

When I first came across the notion of Live Templates, I couldn’t figure out what was ‘live’ about them. Did they need feeding or something? It seems to be an industry-standard term, so I’m no longer devoting much energy to this quandary, but if you were wondering the same, you’re not alone.

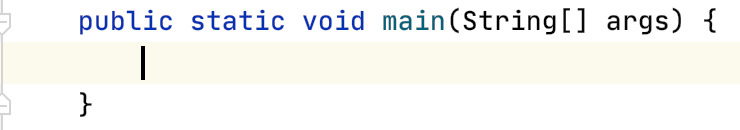

There are lots of types of live templates in IntelliJ IDEA (38 in fact, as I mentioned). There’s the delightful four-finger taps `psvm` which will expand to 39 finger taps of:

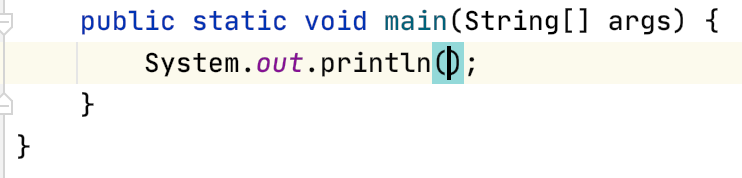

And another of my favourites, also four-finger taps, is `sout` which expands to 20 finger taps:

The Live Templates even determine where the caret appears, which is why screenshots are useful here. There are lots of these ‘non-variable’ Live Templates. They’re quick to use and will quickly embed themselves in your muscle memory. You’ll wonder how you ever wrote:

public static final String

… instead of psfs

However, that’s not all live templates can do; they can also help you with something called ‘parameterised templates’ with variables that you can manipulate.

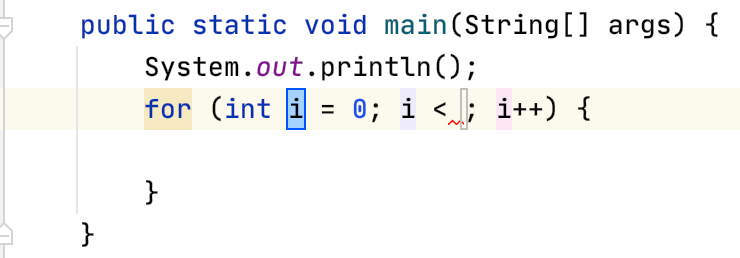

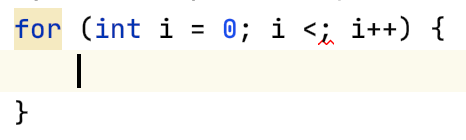

For example, fori gives you a rather lovely for loop template (29 finger taps):

By default, IntelliJ IDEA will put the caret on the first instance of i, and this is so you can change it to your preferred variable if required. If you then hit tab, the editor will jump you to the user input part between the less-than symbol and the semi-colon. Tab again will drop you into the body of the loop so you can step away from those arrow keys.

Other live templates for user input constructs include itar to iterate over elements of an array, itco to iterate over elements of a Collection as well as may other iteration operations. lazy is another win, quite literally, to perform a lazy initialisation.

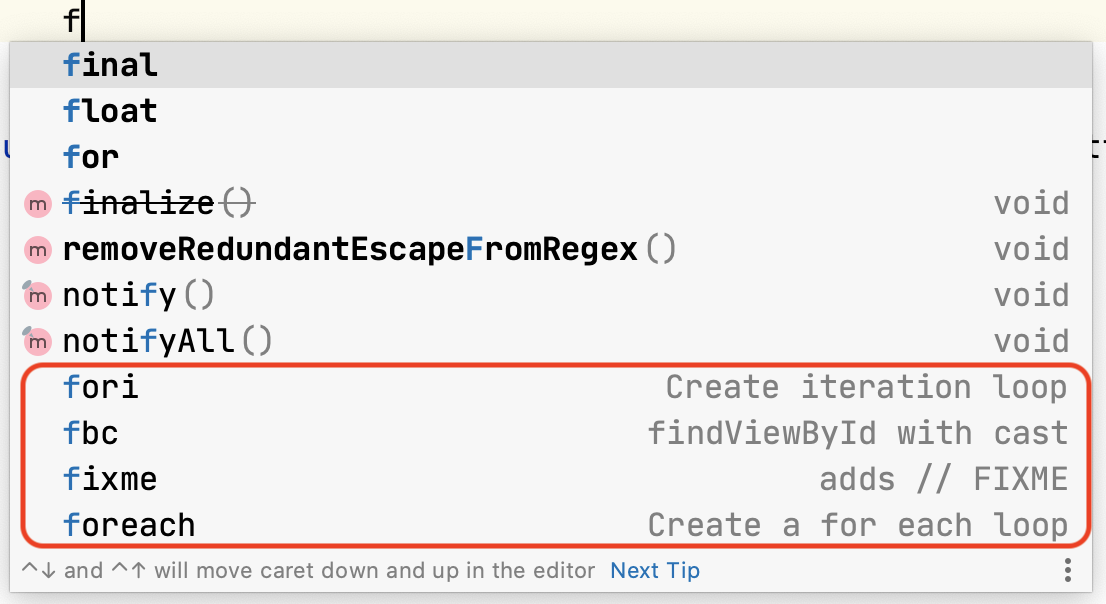

Identifying a Live Template

IntelliJ IDEA is always trying to be helpful. One thing I struggled with was working out what was what when I was typing code. You can spot a live template from the lack of parenthesis and a helpful description. For example, the last four here are live templates, but only one is strictly from Java – fori.

Poking around Live Templates

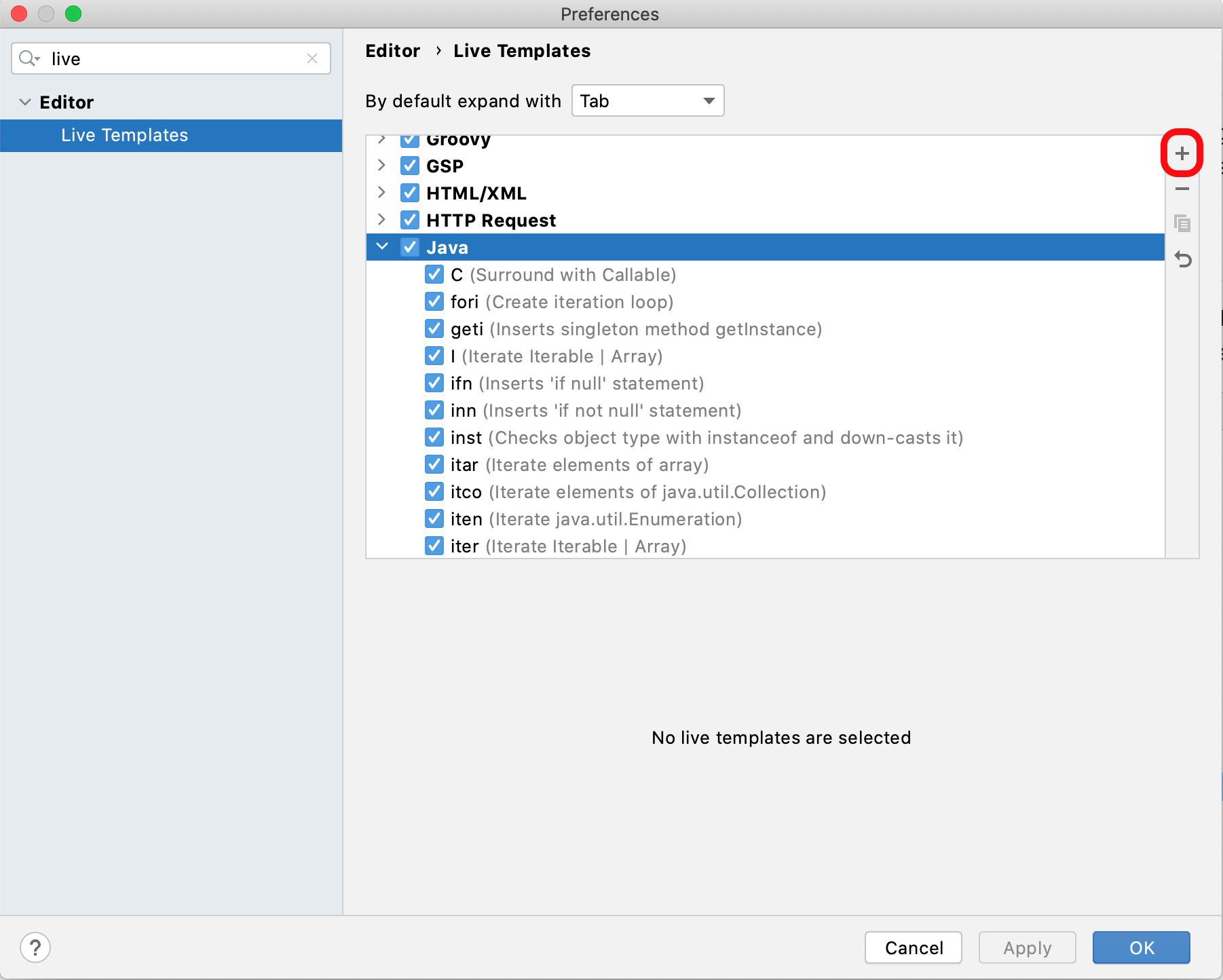

You can take a look at Live Templates from your Preferences using ⌘, on macOS and Ctrl+Alt+S on Windows and Linux then start typing in Live Templates. You’ll see the list split by language. You can have a dig around in here until your heart’s content turning them off (and on again). I found it interesting to check out not only what Java Live Templates there were but also the Live Templates available in the other languages.

Making/Editing/Duplicating a Live Template

Manipulating Live Templates is easy to do in IntelliJ IDEA. As above, find your Live Templates in Preferences and then click this little plus icon:

If you want to duplicate one instead, use the icon a bit further down that looks like paste clipboard.

When you select 1. Live template you can then enter a keyboard abbreviation, a description, and the text that will form your live template.

Live Templates are very flexible in their creation, so here’s a couple of callouts. Firstly, know and use variables wisely. I found these a little bit confusing at first glance, but this documentation removes the mystery nicely and explains what each one does.

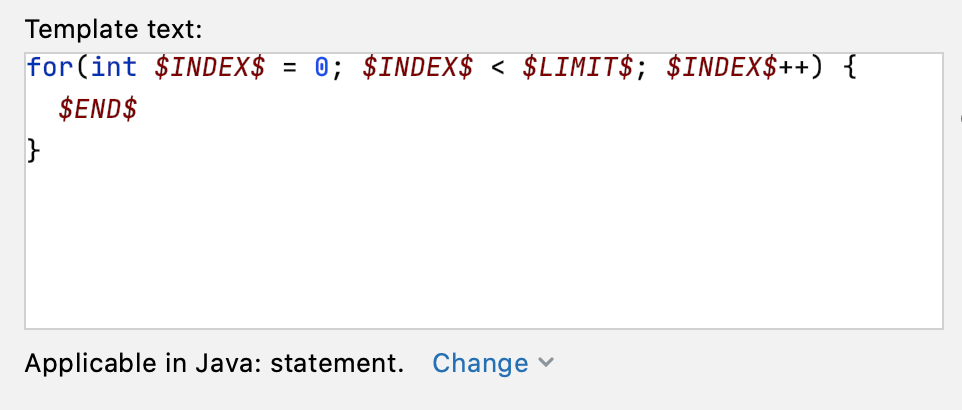

Let’s walk through the fori Live Template to see how it breaks down:

When we use it in a Java class we get this:

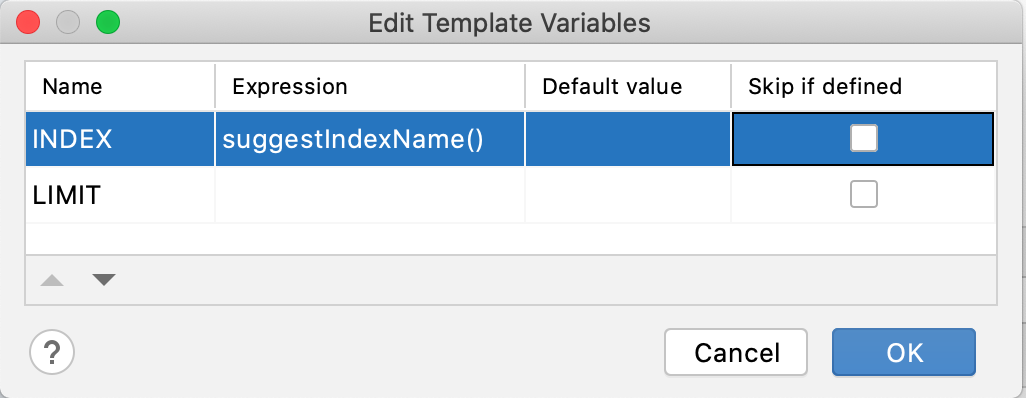

How does that work then? Looking back at the Live Template definition, we can see the Edit Variables button. Clicking it yields this information:

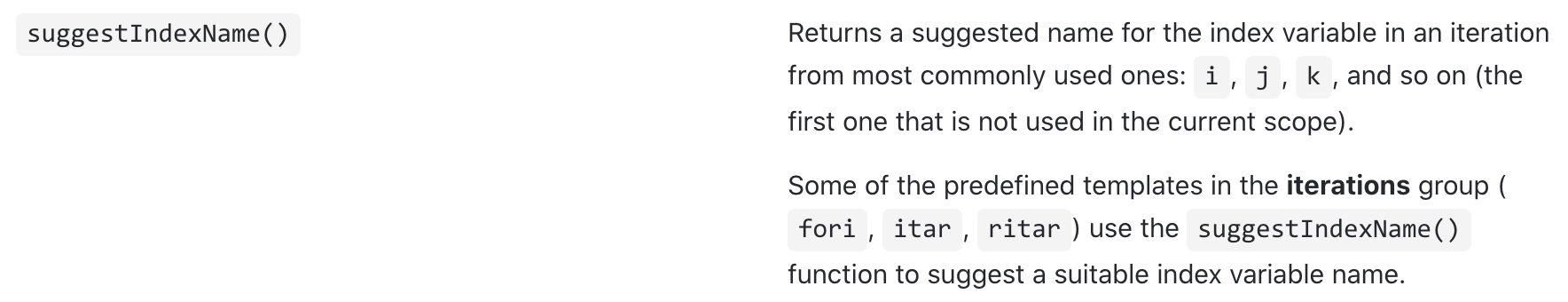

This tells us that the variable $INDEX$ is defined as suggestIndexName() which we can see from the page I pointed you to earlier is defined as:

So $INDEX$ becomes i when we use the Live Template. $LIMIT$ didn’t get a definition in the Live Template so when it’s used in a Java class, that’s where the tab lands for the user to enter a value.

If you leave the value blank, the user can tab to it when the Live Template is used and enter their preferred value, as we saw in the fori example earlier.

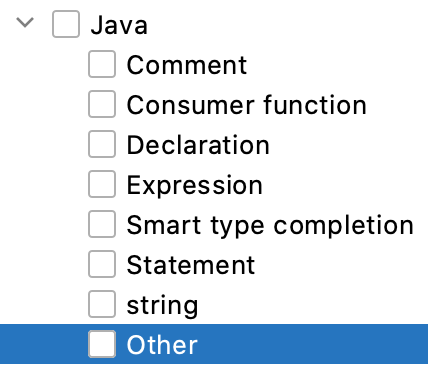

Secondly, define your context carefully; this is where the Live Template will be available for use. For example, these are the available Java contexts:

Our fori example has a context of Statement which makes sense for a for loop:

Now you can go forth and create all the Live Templates that your heart desires and save even more finger taps!

How to Feel Good (about Live Templates)

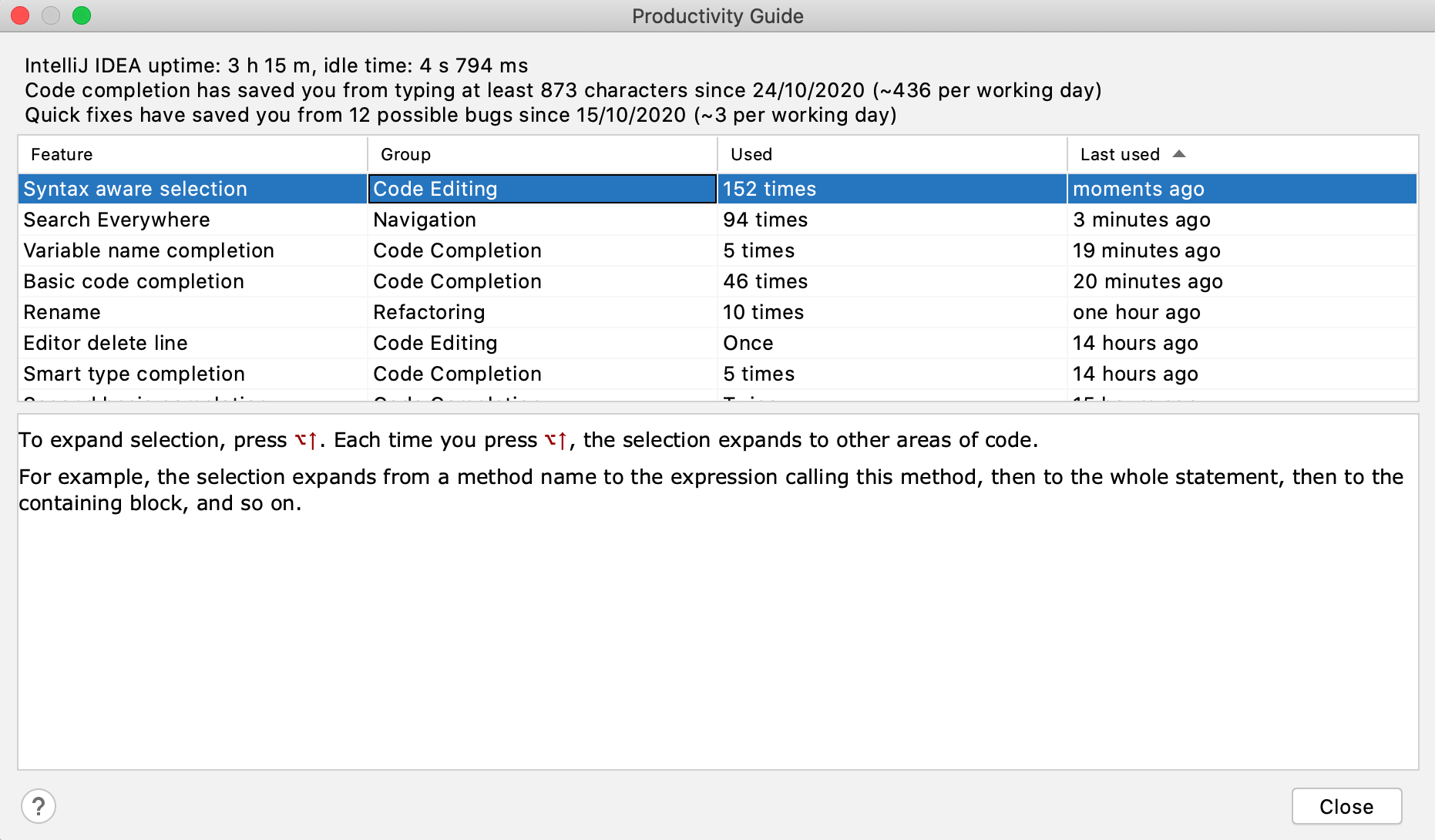

It’s 2020, to be honest, we all need a little extra help with that warm fuzzy feeling this year. I found this thing called Productivity Guide in IntelliJ IDEA. It doesn’t just cover Live Templates; it covers everything that IntelliJ IDEA does to save your finger pads from wear and tear. Mine is pretty feeble because I have to reset my environment multiple times for various screencasts and stuff. I bet your IntelliJ IDEA statistics are substantially more impressive!